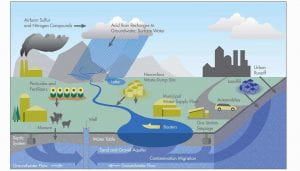

Toxic chemicals in our water is a big issue for many neighborhoods particularly, poor ones. Living in the city of Boston, I’ve noticed and influx of new developments – commercial and residential. With these new developments comes the use for more resources and whether, they are natural or unnatural, the waste seems to end up in the urban waters. The contaminants that flows from one waterway to another such as city streams, rivers, channels or any body of water, ends up in harbors. They range from plastics and medical waste, to trash like alcohol bottles and needles left by party goers and they, ending up in our food, whether seafood or vegetation. How can I affect change?

Toxic chemicals in our water is a big issue for many neighborhoods particularly, poor ones. Living in the city of Boston, I’ve noticed and influx of new developments – commercial and residential. With these new developments comes the use for more resources and whether, they are natural or unnatural, the waste seems to end up in the urban waters. The contaminants that flows from one waterway to another such as city streams, rivers, channels or any body of water, ends up in harbors. They range from plastics and medical waste, to trash like alcohol bottles and needles left by party goers and they, ending up in our food, whether seafood or vegetation. How can I affect change?

Boston’sForte Point Channel which connects to the Boston Harbor

With this thought in mind, I decided first to have conversation with my building (residents and management) to see if they noticed, or maybe get them on the same page. My hope was to get them involve by showing them how this water pollution in our surrounding environment is also having a direct affecting on our health. I also thought that if all went well, we would spread the word to other business as well as residential buildings in the neighborhood (especially new ones). My approach was to see what policies are already in place, address how they are being enforced and/or find new policies that would bring change. Thereby broadening the conversation to deeper issues beyond the surface of just the water, or what we are able to see in our waters. Because what we do not see are the diseases that live right under our noses here in the urban waterways, that destroy humans mentally, physically and economically. Also at the foot of the environmental destruction is any wildlife that lives in the city.

After a conversation with a few neighbors in my building I found out some of them were already involved in neighborhood plans such as planting spring flowers around the neighborhood and creative programs like art near the waterways. This made the conversation much easier to have. I gathered a network of people as well as resources like “Clean Water & Air of Massachusetts” to whom I’ve emailed and awaiting a response. Part of their mission that I felt would help mine was due to one of their slogans that stated “clean air to breath, clean water to drink”. Some other feedback I got from neighbors in my building included women in another organization “Clean Water Action “ , who also contribute toward clean water projects in Boston. I was given contact information as well as an offer to mentor my advocacy because of our likeminded thought. Lastly, after my feedback from neighbors, I found out that the Mayor’s office has a program called “Women’s Advancement”, which helps women with a number of issue from pay equity and racial disparities to women moving ahead in politics. My contact told me that once every few months there is tea or lunch with the Mayor to discuss how to help women in their initiatives. My fingers are crossed for this to happen after “COVID-19”.

With everything I have learned about advocacy in this class as well as read and analyzed the above-mentioned organizations, contacts and their strategies, I came up with two conclusions. One would be to narrow down a list of concerns for a partition to be signed by all of the neighbors who are on the same page. The second would be to go to the next meeting the Mayor is having. This way I could request an official meeting with him to address the issues, thereby bringing the partition in the hopes of enforcing or implementing policies that really work to keep our waters clean.